This post covers material published roughly in the month of January 2015.

A. Charting the Epidemic

A1. Epidemic trajectory

Past/Present. The big news in January has been the apparent rapid decline in case numbers in Sierra Leone, following the equally big fall-off in Liberia in December. Indeed, as of January 23rd, it is being reported that there were only five active, in-care cases of Ebola in Liberia. Not the end, but maybe the beginning of the endgame? The situation in Guinea remains more murky. Although there has been a clear decline in reported cases in Guinea throughout January, there are concerns that some areas are still refusing access to case finders and health educators, and indeed that things may be getting worse. Thus falling reported numbers may not reflect falling actual numbers. Late edit: In the last week of January, case numbers in Guinea ticked up by 10, a 50% increase on the preceding week, and spread to new parts of the country.

While covering the epidemic trajectory, I would be remiss not to mention this WHO overview of the past year. I won’t pretend to have read it all, but it looks like a strong resource for getting up to speed on the epidemic, if with the standard WHO angle on why things happened the way they did.

And finally, I wanted to take a step back to look at the impact of Ebola on non-human primates (NHP). A story rolling along this week suggested that up to one-third of all chimpanzees and gorillas worldwide have been killed by Ebola since it was discovered in humans in 1976. This number appears to have come originally from an unpublished study by Peter Walsh and colleagues. One angle on this was that a vaccine should also be provided to NHPs. Of course, this is the population on which human vaccines are tested, so we should have a fairly good idea whether or not it will work for them (spoiler: the ones currently in development seem to work excellently on NHPs, maybe because at least one of them is based on a Chimp adenovirus? [this last is pure speculation on my part]).

Future. As uncertainty about the overall impact of this epidemic subsides, concern has turned to new areas. At the heart of most concerns is that people will get complacent, allowing the epidemic to smoulder and then potentially re-ignite. Along with the well-publicised fall in interest in the global (social) media interest in Ebola, and concomitant worries about the end of funding for disease control, there already appears to be declining interest and concern within Liberia (see also Containment, Schools below). One marker for this is the ending of “risk allowances” to healthcare workers in Sierra Leone by the end of March.

Ultimately, much of the concern arises from the possibility that Ebola may become an endemic disease. As Peter Piot highlighted (in the last link), this is unlikely in strict terms:

We (humans) are a very bad host from the virus’ point of view… A host that’s killed by a virus in a week or so is absolutely useless.

As a result, case numbers will either rise up (if we do nothing) or die down (as has happened in this outbreak) reasonably fast in each epidemic. However, given ongoing human-bat contact, multiple new outbreaks remains a likely future scenario – which looks a lot like an endemic situation to many.

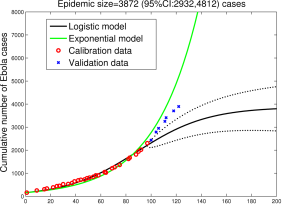

Modelling. There isn’t a lot of modelling left to do in real-time on the epidemic curve as it heads slowly downwards. Which is not to say that there isn’t plenty more modelling to be done. Both of these points, and the opt-repeated one that modelling is hard, especially about the future, were raised and discussed at the Ebola Modelling Workshop in Atlanta last week. Helpfully, all the slides from presentations at the meeting, along with a forthcoming curated summary of the discussions, are available on the workshop website. A must-read for those – like me – who could use some collected wisdom on the topic.

A2. Epidemic parameters

MSF Sierra Leone, under the lead authorship of Silvia Dallatomasinas has published clinical epidemiology data on 489 cases seen in Kailahun between June and October (Dallatomasinas paper). A key finding was that one-third of cases came from outside Kailahun district – largely from Makeni in Bombali district, but also from as far afield as Freetown. For me this emphasizes the importance of mobility for transmission, especially early in the epidemic.

Another interesting insight into transmission dynamics comes from a study by Ousmane Faye and colleagues of transmission chains from March to August in Conakry (Faye paper). The authors show that the great majority of secondary infections were generated in the community – rather than at hospitals or funerals – with over 80% of infections being within families. As Christian Drosten notes in his commentary on the paper, since family sizes vary little by urbanicity, so the reproductive number was no higher in Conakry than in the countryside. Faye et al also show that higher viral loads are associated with greater transmission: hardly shocking, but useful data to accrue.

Concern appears to remain regarding whether ongoing infection could occur via sexual contact with survivors or through breastmilk. While no definitive transmissions have been documented, perceived sexual transmissions are being reported in SL, while concern is being aired that the requirement to abstain from sex for up to six months is not feasible for men.

The issue of potential asymptomatic infection is also rumbling along. Again there are no definitive serological studies of past infections to date, but some small studies suggest that close household contacts test positive without clear symptoms of Ebola. Additionally, one study at Kenema government hospital showed that 22% of suspected Lassa Fever cases presenting from 2001-14 tested IgG/IgM positive for Ebola. Which could beg the question: how specific Ebola tests are?

Another popular topic in the media – for Ebola, but also for almost any other infectious disease, is mutation (on which, please see this great general-audience overview of mutation and infectious disease, in the context of Ebola). So I appreciated this measured article by Abayomi Olabode and colleagues on the Biological arXiv (so not yet peer-reviewed), which highlights that mutations over the past 40 years have led to no apparent shift in functional mechanism of infection. (Olabode paper). I’m sure that there will be lots more on this topic once we have more sequences from this epidemic, but an interesting first step.

And lastly, a quick dive into the zoonotic. Raina Plowright and colleagues note that we believe Ebola (and several other viruses) reach humans via bats, but cross the species barrier only rarely, despite common human-bat interactions. (Plowright paper). Plowright’s paper focuses on Hendra virus, but posits two possible reasons for the rarity of zoonotic events: episodic shedding or transient epidemics (such as those typically seen for SIR-type infections in humans, e.g. measles). I may be far behind the curve on the Ebola-bat literature, but if the world knows as little about Ebola’s cheiropteran lifecycle as I do, this seems to raise some interesting, testable hypotheses.

A3. Visualization

I know that this plot has been around for a bit – since well before Ebola became big news – but it’s a useful benchmark for comparison. Clearly we can quibble about whether 70% is the right CFR, but it gives you an idea of where Ebola sits in the pantheon (or rather the anti-pantheon) of diseases. As you can see, diseases as virulent as Ebola tend not to be very contagious. This is good for us, but also good for the disease – if you kill off all your hosts, there’s not much chance of continuing to exist as a species for very long, especially when you do it as fast as Ebola does.

And in case the various visualization sites I have been pointing you to aren’t quite enough, here’s another blog that focuses _only_ on visualizations for Ebola, by John Tigue. Enjoy.

B. Stopping the Epidemic

B1. Containment

Movement: Speaking as we were of the importance of mobility for transmission, I should quickly update the tale of movement restrictions and associated intensified case-finding in Sierra Leone. At the beginning of January the isolation (quarantine?) of northern districts was extended to ensure that Ebola was under control there. This was followed by “Operation Western Area Surge”, a house-to-house search across several districts, which apparently found well over 200 additional cases. (On a side-note, there is a nice description of the operations of the SL national call centre during September’s “ose-to-ose” campaign in the MMWR). Late in January, the general decline in new cases led to the lifting of inter-district travel restrictions across SL on Thursday 22nd, and a subsequent stream of traffic leaving Freetown. Whether this will lead to an uptick in cases remains to be seen.

Case finding: As the epidemic ebbs, much attention is turning to case finding, the role of contact tracers and other focused prevention activities – in contrast to the earlier focus on broad campaigns. Kai Kupferschmidt has written a nice “day in the life” piece on contact tracers in Bong county, Liberia; while a CommCare app is being used in Guinea to allow real-time reporting and geotagging of potential contacts. Sam Crowe and colleagues have also outlined a system of community-based, event-based surveillance in Bo district, SL. (Crowe paper). The system works through local healthcare workers triggering enhanced monitoring if they hear about clusters of illness, death or traditional burials.

As has been noted, a truly rapid test would be of great benefit to case finders – ensuring false positives can be quickly reassured, and true positives quickly taken into care. Such tests would be even more useful if they could identify infections pre-symptoms: although the feasibility of this remains unclear. Nevertheless, rapid tests appear do appear to be in the pipeline; indeed a “lab-in-a-suitcase” is apparently undergoing testing in West Africa already, using Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) instead of the standard PCR approach. However, various sources have cautioned that while such an approach would be welcome, complex methods that work in the theory, fail in field-testing, and thus such a lab’s usefulness remains to be proven.

Another important aspect of case-finding is that many cases are found only through reports from community members. In this context, a letter from Ruth Kutalek and collagues in the Lancet was educational. (Kutalek letter). The Liberian government, WHO and the World Bank had been considering paying $5 per case reported. A rapid focus-group evaluation of this proposal both rejected the incentive scheme as being disruptive to the community, and highlighted that better case-reporting would require improvements throughout the care continuum that made entering into care a more feasible and acceptable proposition. Which buttresses other reports highlighting the importance of listening to local communities, to maximize the chances of affecting behaviour change and ending the epidemic.

Isolation: While case finding may be the on-the-ground flavour of the month, there remains a great deal of academic interest in how best to control the epidemic in the healthcare or para-healthcare setting.

One important paper this month was published by Stefano Merler and colleagues (building from the work of Alex Vesgipnani’s lab at Northeastern University). (Merler paper). The team has build a realistic model of the population structure in Liberia at the individual level, and then calibrated epidemic parameters to observed outcomes up to August 2014. They use the model to show the likely impact of various interventions – safer burials, building of ETUs, etc. One key finding of theirs is that local transmission is key to disease propagation – although Gerardo Chowell and colleagues note that long-distance transmission has also been key (and also see Dallatomasinas’ paper above). Chowell and Hiroshi Nishiura also provide both an overview of network models and a plea for spatiotemporal data in reflecting on the publication of John Drake’s work (covered previously when on the arXiv) in PLoS Biology. (Drake paper).

On a side-note, Merler et al find a 40/30/10 split in secondary cases arising from hospitals/home/funerals; this is very different from the numbers seen in Conakry by Faye et al (see above). Whether this is due to different methodologies or truly different dynamics, this seems like a very interesting question that might be crucial to understanding how epidemic dynamics differ by country.

I also appreciated a blogpost by Silvia Munoz-Price, who highlighted the unusual situation in which clinical staff are seeking out Infection Control professionals, in contrast to their usual efforts to avoid all advice on the subject. She doesn’t provide any quick answers on how to sensitize HCWs in other settings – aside from breeding an HCW-preferring strain of C difficile – but the issue is one that has broad resonance for healthcare provision in the age of drug-resistant bugs.

Community-based care continues to be raised as an important part of the care continuum, given its cost and speed benefits over building Ebola Treatment Centres (ETC). Michael Washington and colleagues used a simple SEIR model to estimate the relative benefit of increased ETC and CCC (community care centres) in Montserrado and Lofa counties, Liberia, in September/October last year. (Washington paper). Their models suggested that both were useful individually, and even more so jointly, but that CCCs were likely to have a greater impact if one approach had to be prioritized. In this context, Sharon Salmon and colleagues’ letter highlighting that the Liberian government and NGOs trained up thousands of community volunteers for basic preventative care (and I believe Sierra Leone did similarly) is informative and likely an important component of control efforts.

And finally, a(nother) paper by Nishiura and Chowell compares/contrasts the dynamics of Ebola to that of Influenza, highlighting that the direct-contact mode of transmission of Ebola means that even though the R0 of these two diseases is roughly similar, the speed of epidemic growth is much slower (and the potential for control through social distancing much higher) for EVD. (Nishiura paper).

Safe burials: While safe burials may well have been an important factor in controlling this epidemic, they have not always been appreciated – especially when they were not conducted in a culturally sensitive, or just a sensitive, manner. In this context, it was interesting to me to read Carrie Nielsen and colleagues’ outline of how an SOP for safe and respectful burials was drawn up in Sierra Leone in October, as control efforts were rapidly expanded, and how efforts were then monitored and adjusted as needed. (Nielsen paper). In contrast, Liberia took a crematory approach to safe management of deceased bodies, and as this journalist’s report from Monrovia highlights, this has led to distrust, unhappiness and potentially future social upheaval as families are left without the ability to conduct key social/cultural practices with their deceased relatives. One of these countries looks like it has done a better job on this front.

B2. Treatment

Drugs: Trials of antiviral drugs as Ebola treatments continue in several parts of West Africa through MSF facilities. A trial of favipiravir in Guinea is being run by National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) – details on dosing being used are here; a trial of brincidofivir is being run by University of Oxford researchers at the MSF ETC in Paynesville, Monrovia (stop press: the brincidofivir trial appears to have been stopped; reasons for this are unclear, maybe due to the low number of patients enrolled). In line with past MSF comments, these are being run without a control group (one assumes using historical outcomes as controls). There will also be a trial of convalescent serum (i.e. part-blood transfusions from recovered patients) in Conakry starting soon (MSF overview here). On this last I would highlight a letter by Melanie Bannister-Tyrrell and colleagues highlighting the potential stigma for both donors and recipients in the context of passing blood between people. The importance of local knowledge, once more.

Also, I would be remiss not to highlight in light of my reporting last month on allegedly unethical testing of amiodarone as a treatment for Ebola at Emergency’s ETC in Freetown. Emergency have responded very firmly to such allegations in a blogpost. As well as contesting many of the facts in the case, the author(s) appear to believe that one reason for opposition to amiodarone’s use is its out-of-patent status and the consequent lack of profits available for its use. I’m not sure which side in this argument holds the greatest validity, but I wanted to make sure I was showing you all the arguments.

B3. Vaccines

Before diving into the practicalities, I noticed that Yazdan Yazdanpanah and colleagues (whom I last saw read while working on HIV cost-effectiveness a decade ago) have put together a brief overview of the intracellular lifecycle of EVD. (Yazdanpanah paper). A wonderful introduction for those of us with little knowledge of at the cellular level.

Now, on to those practicalities. When last we spoke, two vaccines (GSK/NIAID’s ChAd3 and NewLink/Merck/CanGov’s VSV) were in phase II trials, although the VSV trials had been put on hold due to some non-negligible joint pain. The ChAd3 team reported immunogenicity this past week in the NEJM.

The VSV trial resumed in the first week of January after the Christmas/holiday break, at much lower doses. A third product (led by Janssen, a Johnson & Johnson company) has also now begun trials too.

Of course, the real action will happen once trials reach phase III: the search for efficacy. Fortunately, a key challenge to proving the efficacy of any vaccine at the present time: the lack of new infections in the three countries. Clearly this is a good situation to be in from the perspective of the current outbreak; however without evidence for which vaccine(s) work now, planning for future outbreaks will be hampered.

In order to maximize the chances of seeing any true effect (i.e. maximize power) each of three teams putting together phase III trials (one per country) are considering new methods and evolving their plans very rapidly. The first trial will be in Liberia – starting in the first week of February. This will be run in conjunction with the NIH, and will involve three arms – quite probably two treatments (AdCh3 and VSV) and one control involving vaccination for something other than Ebola – with around 9,000 participants in each arm. It will be a classic Randomized Controlled Trial.

The second trial will be run by the CDC in Sierra Leone. The exact methodological details remain sketchy, but the population will be high-risk individuals involved in the Ebola response (ETC workers, burial teams, case finders) and the method will be a cluster randomized trial of some description (it was going to be a Stepped Wedge design; I gather this plan has been changed now). If there prove to be very few cases in Liberia, the SL and Liberia trials may get merged to improve power.

The third trial is decidedly innovative: it will involve “ring vaccination”. In this approach – previously used as a vaccination roll-out strategy, one vaccinates the contacts (approximately 50 local residents here) of each case found, but at different speeds: either immediately, or after 4-8 weeks. This allows a difference in effect to potentially be seen, without denying anyone a chance to get some kind of treatment. It also should help to control the epidemic – something that may be most urgent in Guinea.

And if you thought all that wasn’t complicated enough, CIDRAP at the University of Minnesota and the Wellcome Trust put together a report on potential roadblocks, Bruce Lee and colleagues at the International Vaccine Access Center at John’s Hopkins highlighted seven possible vaccine roll-out issues and two moderators at ProMed added a couple more of their own. Getting to vaccination is a long road that is being heroically shortened for this epidemic, but that doesn’t make it a short path.

B4. Social factors/impact

IMF debate. Last month I noted the publication of a commentary by Alex Kentikelenis et al. placing some of the blame for the size of the West Africa outbreak on the IMF’s past policies. The IMF and Chris Blattman responded on the Monkey Cage blog. And then things took off. On the Monkey Cage, Adia Benton and Kim Yi Dionne highlighted some key readings on how the IMF affects social spending, Alex responded to Chris, and Chris responded again. Other notable contributions to the debate included one by Morten Jerven and another by Ken Opalo.

The takeaways are many, and will vary depending on your subjective view of the situation. As someone who sees everything in shades of grey (no, that link is not to anything EL James related), I can see how the IMF has historically limited the scope for social expenditure in countries it has aided, but can also see how this limitation may have had beneficial knock-on effects on the countries in question, and how existing national political structures might have limited such spending even in the absence of IMF guidelines/strictures. Bottom line: as several commenters have said, the level of evidence in this debate could probably be improved. If, you know, anyone has the spare time and money to get that done…

Education: One impact of this outbreak that I have not been discussing much is the closure of schools. Aside from loss of learning, there have also been concerns within the affected countries about possible increases in teenage pregnancy [refs] All three most-affected countries are now considering re-opening schools, as a very public and visible sign of confidence that the worst is over.

Liberia is planning to reopen in February – although there is concern about children coming to school when sick, potentially because they are not able to understand/communicate their risk, or keep a social distance from classmates (this echoes what I’ve heard about treating young children at ETCs). There are also plenty of logistical problems with enrolling more than six-months’ worth of new pupils. And then of course this has become a political issue, with Senator George Weah (yes, that George Weah) criticizing the move. Upshot: schools are now set to open mid-February.

The minister of Education in Sierra Leone said on Jan 9th that it wouldn’t reopen until the epidemic is over, however by the 21st they have now slated the restart to be in March. Guinea was planning to reopen as early as Feb 2nd, but that now appears likely likely to be pushed back too.

Agriculture: I have seen stories ranging from “everything’s falling apart” to “it’s not really that bad”. In this context, this piece by Lisa Hamilton in The Atlantic provides a nice overview of the current situation: not great, could get worse is the gist I took away.

And finally, couple of things I wanted to include, but haven’t got a clear category for:

- A brief insight into a huge future issue: what happens economically after the epidemic ends? It’s not a pretty question, but it is a necessary one.

- A symposium on how Ebola looks from the Political Science world. There is more than one Health/PoliSci person in there worth reading.

C. Journalism

A couple of notable general-consumption longform pieces that caught my eye in the past month:

Finally, I have seen a few more first-person accounts that I would argue are worth a few minutes of your time:

–

If you have seen something I’ve missed (or links are broken), you can reach me @harlingg. And as ever, thank you to all those on whose intellectual shoulders I am standing.

There are nine previous posts in this series and a summary of data/research sources.